The Gestapo was also enlisted in [the Third Reich’s] attempt to undermine the Republican government. Cooperation between Spanish police and the Gestapo had been initiated in 1934 in the form of proposing directly exchanging information about dealing with Communist activities.19

This interest of social control led to the Spanish Ambassador in Berlin being instructed on 14 March 1935 to seek formal cooperation between the Gestapo and the Spanish political police for this purpose,20 to which the [Reich’s] Embassy in Madrid replied in the affirmative on 11 September.21 The stage was thereby set for [the Third Reich’s] penetrating into Spain in order to advance the interests of the régime, which were later to be adopted by the [parafascist] régime after the end of the Spanish Civil War.

[The Third Reich’s] efforts to expand [its] political influence across Europe, and the rôle of police like the Gestapo in that process, were not hidden. Political refugees from [the Reich] published a survey of hostile German activities in Europe in Paris in 1935, Das Braune Netz. Wie Hitlers Agenten im Ausland arbeiten und den Krieg vorbereiten [The Brown Net: How Hitler’s Agents Abroad Operate and Prepare for War].

This book highlighted the rôle of espionage in [Fascist] activities, stating that 48,000 agents were abroad, and reported on German Propaganda and the operations of the Aussenpolitische Amt der NSDAP (Foreign Political Office of the NSDAP) in collaborating with international anti‐semitic organisations and minority movements to undermine foreign governments through sister organisations known as Ortsgruppen.22

[…]

While the Gestapo was not involved in the preparations for an anti‐Republican military coup,23 it became involved in Spanish internal affairs after during the Spanish Civil War that began in July 1936 and lasted through April 1939. The [parafascist] police developed by Franco in his Nationalist zone was established on the pattern of the police organisation in [the Reich].24

The Gestapo thereby trained the Spanish police and security service,25 the political police, to contribute to maintaining the Franco régime in control of Spain, just as the Gestapo in [the Reich] was charged with investigating and suppressing all forms of anti[fascist] tendencies throughout [the Reich] and then later in the [Fascist‐]occupied territories.

The Gestapo passed on what it knew — it was tasked with taking action against potential political opposition by operating as an information gathering and law enforcement body that gradually assumed offensive functions and an overtly political rôle that was hardly subject to judicial restrictions.26 While the Gestapo represented the [Reich’s] most important element for enforcing policy and implementing a system of terror that reinforced compliance with [Fascist] doctrines and [Reich] law,27 the methods and tactics it used were exported to Spain.

Gestapo agents were dispatched Spain for these training purposes28 under the guise of contributing to the struggle against the alleged danger of worldwide communism through instructing the Spanish police about its methods and proceedings.29 These circumstances concurrently contributed to reinforcing the authority of the [parafascist] régime that would in turn be maintained in the Axis orbit.

[…]

The influence of the Gestapo also extended to pursuing German nationals abroad. Hermann Göring, who had created the Gestapo while serving as the Prussian minister of the interior, issued an order on 15 January 1934 to the Gestapo and the frontier police that they were to keep records of political émigrés and Jews90 who were living abroad, and were to be arrested or sent to concentration camps upon their return to [the Reich].

These exiles were constantly spied on, and were especially pursued by the Gestapo following the entry of troops wherever [the Reich] invaded.91 Violations of [Reich] law in Spain by German émigrés were investigated, regardless of their having acquired Spanish nationality, and were to be taken into custody92 when their actions were considered to be hostile to the [Reich].

Police supervision on the [Reich’s] diplomatic staff in Spain was likewise maintained for the same purpose.93 Jewish refugees residing in Spain likewise faced the danger of being deported to [the Reich] when General Franco gave his approval for this measure in 1941,94 which would have come under the jurisdiction of the Gestapo there if this measure had been put into practice.95

According to American intelligence reports, the local Gestapo agent in Mallorca named Seyfarth tracked down Jewish refugees amongst the some seven Germans who lived there, forcing some to return to [the Reich].96

Spanish police also cooperated with the Gestapo to repatriate German nationals who were deserters, members of a foreign legion, emigrants, including certain Jews who were of particular interest to the régime, as well as individuals who were wanted by the [Reich’s] police.97

(Emphasis added. Click here for a summary.)

Quoting Alejandro Baer and Pedro Correa in A Companion to the Holocaust, page 399:

A second line of research has focused on the cooperation between the Spanish and the [Reich’s] police, which enabled the Gestapo, in Patrick Bernhard’s words, “to hunt for Jews on Spanish territory.”8 A significant example of this police cooperation against Jews is the case of the German‐Jewish refugees who found shelter in the Spanish island of Mallorca following [German Fascism’s] rise to power in 1933.

From late 1940, these refugees were rounded up in Madrid and forced to choose between migrating to a third country (something virtually impossible for German‐Jewish refugees at the time) or suffering internment in Spanish internment camps.9

Other antisemitic measures suggesting broader police collaboration include the so‐called Archivo Judaico. Upon its creation in May 1941, the Spanish police received orders to register all national and foreign Jews living in Spain and to specify their “personal and political leanings, means of living, commercial activities, degree of dangerousness” as well as other security considerations.10

These measures seem to imply plans for further collaboration on the persecution of Jews at a time when Spain was still considering entering the war alongside [the Reich]. Similarly, there is evidence that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Spanish police handed over Jewish refugees to the [Fascists] on the other side of the Pyrenean border, even though these deportations were never large in scale.11

The shifting balance of power during World War II resulting from the Allies’ North African landings in November 1942 and the fall of Mussolini’s régime the following year, however, obliged Franco’s Spain to be more consistent with its “neutrality.” This situation translated into an increasingly tolerant attitude toward the Jews, even though antisemitism itself would remain an essential element of the régime’s rhetoric for years to come.

Click here for events that happened today (March 12).

1876: Wilhelm Frick, Axis Minister of the Interior, was born.

1933: Gedern’s gentiles assaulted the local Jews, severely injuring one and forcing the victim to stay hospitalized for the following year. Coincidentally, the Fascist ruling class established two legal national flags: the reintroduced black‐white‐red imperial tricolor and the NSDAP’s swastika flag. Oranienburg north of Berlin became the site of the Third Reich’s first concentration camp.

1935: Reich officials Alfred Rosenberg, Paul von Rübenach, and Konstantin von Neurath in Berlin spoke with their Imperial counterparts in Tōkyō.

1937: Georg von Küchler became the commanding officer of 1st Military District with personal command over I Corps.

1938: Berlin declared—then affected by marching troops across the frontier—Anschluß with Austria. Hours later, the Reich’s Chancellor visited Linz in the recently annexed Austria region of Germany; he met with the Berlin‐installed Austrian Chancellor Arthur Seyß‐Inquart at this city to discuss details of the occupation. Ousted Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg came under house arrest.

1939: The Reich’s leaders demanded that Slovakian leader Jozef Tiso to visit Berlin, where they told him to declare Slovakian independence immediately otherwise the Reich would withdraw its support for such a movement. Likewise, Imperial troops began advancing from Hubei Province, China toward Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, China.

1940: The Fascists forced a transport of one thousand German Jews to march through cold weather toward the Lublin Ghetto, and seventy‐two of the victims died of exposure. That aside, the Reich’s Chancellor met with Colin Ross, whom said Chancellor considered to be his top adviser on the United States. Ross obliviously told him that the United States, run by Jews, had imperialist tendencies in terms of foreign policy. Ross also advised him that Franklin Roosevelt, who had come to power around the same time as German Fascism, was jealous of the Chancellor’s greater success thus was plotting with the Western Allies to defeat the Reich. Coincidentally, Reich Foreign Minister Ribbentrop continued his meeting with Mussolini in Fascist Italy, setting up a conference between Schicklgruber and Mussolini to be held some time on or after March 19, 1940.

1941: Benito Mussolini visited Axis troops in Albania to bolster morale, and Axis submarine U‐37 sank Icelandish trawler Pétursey with surface weapons 300 miles south of Iceland. Axis bombers attacked Merseyside (containing the city of Liverpool), England, sinking eight merchant ships, destroying one floating crane, and slaughtering 174 people in the town of Wallasey.

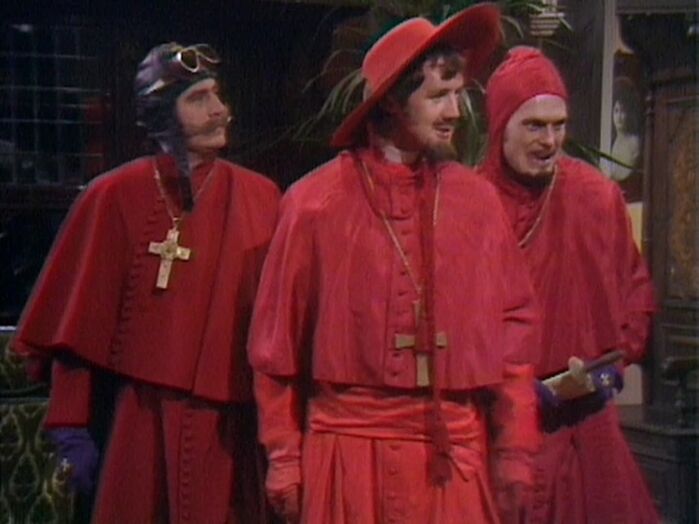

The Spanish Police…? 🇪🇸

You may say that was rather UNEXPECTED!!